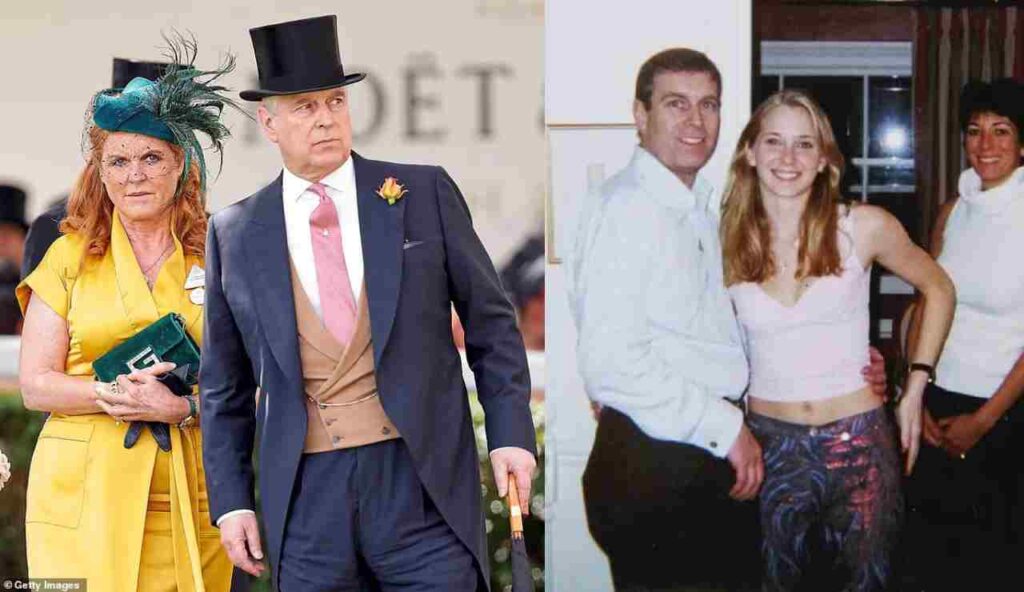

Andrew, stripped of titles and patronages, at least has the numb shell of royal protocol to cushion the fall. Sarah has only her own reflexive self-blame. “What if I hadn’t written? What if I’d cut him off sooner?” she mutters, looping the same questions until aides swap glances. The daughters she adores—Beatrice, Eugenie—urge a “strategic rebrand”: motherhood, wellness, female positivity. Sarah nods, but the words feel like costume jewellery against her skin.

Outside, satellite trucks idle on Windsor Great Park. Publishers have quietly shoved her forthcoming children’s book from October to late November; Waterstones staff whisper that even November feels optimistic. HarperCollins will not return calls. A memoir? “Toxic,” one editor says off the record. “We’d need haz-mat gloves.”

Night brings no relief. Royal Lodge, once a refuge where divorced ex-lovers reinvented themselves as eccentric housemates, now feels like a set waiting to be struck. Corgis Muick and Sandy click across the parquet, the only sound save for the occasional thud of another delivery hitting the doorstep. Buckingham Palace has confirmed the dogs will “remain with the family,” a phrase Sarah clings to: some living creature still counts her as kin.

She sketches escape routes on the back of unpaid invoices—Dubai, Switzerland, the Costa del Sol flat a friend still owes her. “I’ve lived on the hoof before,” she sighs, remembering the post-divorce years of hand-to-mouth hustle. Yet the same question paralyses her: flee to what? The lecture circuit is closed; charity boards have blacklisted her; television dropped her within hours of the headline. Even the ghost-written mea culpas that once paid school fees are unsellable when the crime is correspondence with a convicted predator.

Andrew, stoic in the smoking room, studies military-history podcasts and pretends the silence is voluntary. They speak mostly through Post-it notes: “Please clear garage by Jan 15.” “Corgi worm tablets ordered.” The calendar shrinks toward the date the Crown Estates formally reclaim the keys. Removal vans, she is told, will need three runs; the attic alone holds three decades of souvenir teddy bears and unopened corporate freebies.

At 3 a.m. Sarah stands in the garden, dew soaking her mismatched socks. She pictures a tiny apartment somewhere warm, no crest on the crockery, no columnists cataloguing her failures. For a moment the fantasy steadies her breath. Then Muick noses her ankle, and the future collapses back into the simple, urgent question: who will walk the dogs if she boards the next one-way flight?