A Town’s Journey through Time

By Editor-in-Chief, Tab2Mag

Asif Ghazali

In the heart of West London, in what was once the ancient county of Middlesex, lies Southall—a town whose story reads like a vivid chronicle of Britain’s post-war transformation. From its centuries-old horse markets echoing with the sounds of traders and travellers to its current identity as “Little Punjab,” Southall’s journey represents one of the most remarkable demographic and cultural shifts in modern British history.

The Old Southall: A Market Town’s Heritage

Long before tower blocks and curry houses lined its streets, Southall was a traditional English market town with a royal charter dating back to 1698, when King William III granted Francis Merrick permission to hold a cattle market. For over three centuries, this market became the lifeblood of the community, drawing farmers, traders, and members of the travelling community from across the region.

Every Wednesday, the distinctive sounds of horse trading filled the air. Dealers would arrive at dawn, their carts laden with horses, pigs, harness, and vehicles. The market wasn’t just a place of commerce—it was a meeting ground, a social hub where generations of families built their livelihoods. Old-timers still remember the smell of livestock mixing with the morning mist, the rhythmic clip-clop of hooves on cobblestones, and the distinctive calls of auctioneers conducting their business.

The town also boasted elegant cinemas like the Palace Cinema, which opened in 1929 with its striking Chinese-style architecture designed by George Coles. With its distinctive pagoda roofs and dragon finials, it stood as a testament to Southall’s prosperity and its place as a thriving suburb of the expanding metropolis of London.

The First Wave: 1950s – Seeds of Change

The story of Asian Southall begins quietly in 1950. That year, the first group of South Asian men arrived, reportedly recruited to work in a local factory owned by a former British Indian Army officer. These pioneers could hardly have imagined that they were planting the seeds of what would become the largest Punjabi community outside India.

Post-war Britain was hungry for labour. The newly created National Health Service needed doctors and nurses, the textile mills of the north required workers, and most significantly for Southall, the rapidly expanding Heathrow Airport—just three miles away—demanded a steady stream of employees. The proximity to Heathrow proved crucial; it offered stable employment and symbolically represented a gateway between the old country and the new.

These early arrivals were overwhelmingly men from the Punjab region of India and Pakistan—farmers’ sons, ambitious young men seeking better opportunities, former soldiers who had served in the British Indian Army. They worked hard, sent money home, and lived frugally in shared accommodation, always with the intention of eventually returning home. Few suspected that Southall would become home.

1960s: Foundations of a Community

By the early 1960s, the trickle had become a steady stream. The 1962 Commonwealth Immigration Act loomed on the horizon, and families rushed to Britain before the door closed. Women and children began arriving to join the men who had established a foothold, transforming what had been a bachelor community into a living, breathing neighbourhood.

The character of Southall’s High Street began to shift. The R. Woolf Rubber factory employed a workforce that was 90% Asian by 1962. The Asian Workers’ Association, established to protect workers’ rights and provide a voice for the community, opened its doors. Meanwhile, traditional English establishments watched these changes with mixed reactions—some with curiosity, others with barely concealed hostility.

1968: The Culinary Pioneers

Your memory serves you well—1968 was indeed a landmark year. Among the terraced houses and traditional English shops, two restaurants opened their doors: one Pakistani, one Indian. These weren’t just eating establishments; they were cultural beacons, places where homesick immigrants could taste the flavours of home and where curious locals could venture into something exotic and unfamiliar.

The traditional market traders, who had sold English vegetables and meat for decades, began to notice the demand for different produce. Gradually, stalls started stocking okra, bitter gourd, fresh coriander, and huge bags of basmati rice. The aroma of spices began mixing with the traditional smells of the old market.

1970s: The Bollywood Years and Rising Tensions

The early 1970s brought both cultural blossoming and violent confrontation. The Palace Cinema, which had closed as a mainstream venue in 1971, reopened as the Odeon, then the Odeon, and finally—from May 1972—as the Liberty Cinema, showing exclusively Bollywood films. For the first time, South Asians didn’t have to travel to central London to see films in Hindi, Punjabi, or Urdu. The Liberty became more than a cinema; it was a gathering place where the community could maintain its cultural connections.

The Century Cinema and later the Dominion also began showing Indian films, replacing popcorn with samosas and masala chai. Young people would queue around the block for the latest Amitabh Bachchan or Rajesh Khanna blockbuster. The traditional English cinemagoers had long since moved on or moved away.

But this was also a decade of darkness. By 1976, two-thirds of Southall’s children were non-white, and the demographic shift triggered a racist backlash. The British National Party and the fascist National Front began targeting Southall with propaganda and intimidation. On June 4, 1976, eighteen-year-old Gurdip Singh Chaggar was murdered by racist thugs on Southall High Street. When a young man named Suresh Grover asked a policeman what had happened, the officer dismissed it with the chilling words: “It was just an Asian.”

This murder galvanized the younger generation. Within days, the Southall Youth Movement was born—young British Asians who refused to accept the quiet tolerance their parents’ generation had adopted. They took to the streets, organized protests, and stood up to the National Front’s provocations.

The violence culminated on April 23, 1979, when the National Front scheduled a meeting at Southall Town Hall on St. George’s Day. Over 10,000 residents and supporters marched in protest, met by 1,200 police officers in riot gear. In the chaos that followed, Blair Peach, a New Zealand teacher and activist, was beaten to death by police officers. The tragedy shocked the nation and marked a turning point in British attitudes toward race relations.

1980s: Consolidation and Identity

By 1982, 65% of Southall’s 83,000 residents were of Asian origin. The transformation was no longer gradual—it was complete. The Liberty Cinema closed in 1982, a victim of the home video revolution. Suddenly, every household could rent video machines and Bollywood films from the proliferating Asian video shops. The number of VCRs owned by British Asian families in Southall reportedly rivalled ownership rates in Japan.

The last traditional English pubs began changing hands or closing their doors. The Three Horseshoes, designed by architect Nowell Parr, hung on until 2017, but it was an exception. The old fish and chip shops were replaced by sweet centres selling jalebis and barfi. The horse market, that ancient symbol of old Southall, continued every Wednesday, an anachronistic reminder of what had been, populated now mainly by Irish travellers while Asian shopkeepers served customers all around them.

1990s-2000s: Little Punjab Arrives

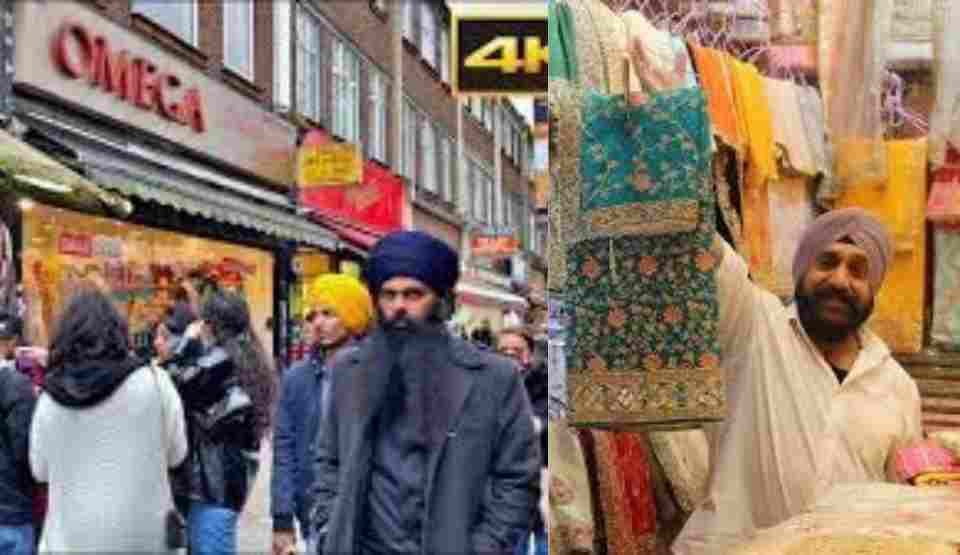

The turn of the millennium saw Southall’s transformation reach its apotheosis. The high street became unrecognizable from forty years earlier. Shop signs were now predominantly in Punjabi, Hindi, and Urdu. The smell of fresh samosas, pakoras, and tandoori chicken permeated the air. Gold jewellery shops gleamed with intricate designs catering to wedding shoppers. Sari shops displayed rainbow arrays of fabrics. Gurdwaras (Sikh temples) had become architectural landmarks—the Gurdwara Sri Guru Singh Sabha became one of the largest Sikh temples outside India.

The famous horse market, which had run for over 300 years, finally closed its gates forever on August 1, 2007, ending an era. For some old-timers, it felt like the final chapter of old Southall had closed.

Radio stations like Sunrise Radio and Desi Radio broadcast in Punjabi. Newspapers like Des Pardes served the community. The entire infrastructure of daily life now catered to Asian culture. English-language services became the exception rather than the rule.

The Palace Cinema, after years as a derelict market building, was rescued by businessman Surjit Phander and reopened in 2001 as the Himalaya Palace, a state-of-the-art three-screen Bollywood cinema. Though it closed again in 2010 due to competition from home entertainment, its Grade II* listed building stands as a monument to Southall’s unique journey.

2010s-Present: A Complete Transformation

By the 2011 census, the statistics told an extraordinary story. In Southall Broadway ward, 93.7% of residents were from Black, Asian, and minority ethnic backgrounds—the lowest proportion of white British residents anywhere in the United Kingdom. In the broader Southall area, 76.1% were Asian, 9.6% Black, and just 7.5% white.

Your observation is not an exaggeration: walking through Southall today, one might see only a handful of white British faces among hundreds of Asian residents. For the few remaining English families from the old days, the disorientation is real. Some describe feeling like strangers in their own hometown, walking streets where they no longer understand the shop signs, where the butchers sell halal meat, where the sounds, smells, and sights are entirely different from their childhood memories.

The high street throbs with energy—Bhangra music pulses from shops, street vendors sell fresh sugarcane juice, and the aromas of street food fill the air. The architecture remains largely British, but everything else has transformed. Even the ancient market, once the site of horse trading, is now a vibrant Asian bazaar selling everything from exotic vegetables to the latest Bollywood DVDs.

Reflections on a Transformation

How did this happen? The answer lies in the convergence of several factors:

Economic opportunity: Heathrow Airport’s proximity provided steady employment for generations of Asian families.

Chain migration: Once established, communities attracted relatives and friends from the same villages in Punjab, creating tight-knit networks.

White flight: As the Asian population grew, many white British families moved to outer suburbs, accelerating the demographic shift.

Cultural infrastructure: Restaurants, temples, cinemas, and shops created a self-sustaining community where English was no longer necessary for daily life.

Resilience: Despite facing racism, violence, and discrimination, the Asian community not only survived but thrived, establishing successful businesses and strong family networks.

Policy changes: Immigration laws in the 1960s and 1970s, while intended to restrict migration, actually accelerated family reunification before doors closed.

Today’s Southall stands as both a success story and a cautionary tale—a testament to immigrant determination and community building, but also a reminder of Britain’s struggle with integration and multiculturalism. For Asian residents, Southall is a vibrant, thriving community where they can maintain cultural traditions while building British futures. For the remaining white British residents, it represents a loss of the familiar, a hometown that has become unrecognizable.

The horse markets are gone. The English pubs have closed. The fish and chip shops are memories. But Southall itself thrives—no longer an English market town in Middlesex, but Little Punjab in London, a place where two worlds met, clashed, and ultimately created something entirely new.

This transformation—from Francis Merrick’s 1698 market charter to today’s bustling Punjabi high street—represents one of the most complete demographic transformations in British urban history. Whether viewed as triumph or tragedy depends on who’s telling the story.

About the Author: Editor-in-Chief of Tab2Mag. This article draws on historical records, census data, and the living memories of Southall’s transformation over seven decades, documenting how a traditional English market town became the heart of Britain’s Punjabi diaspora.