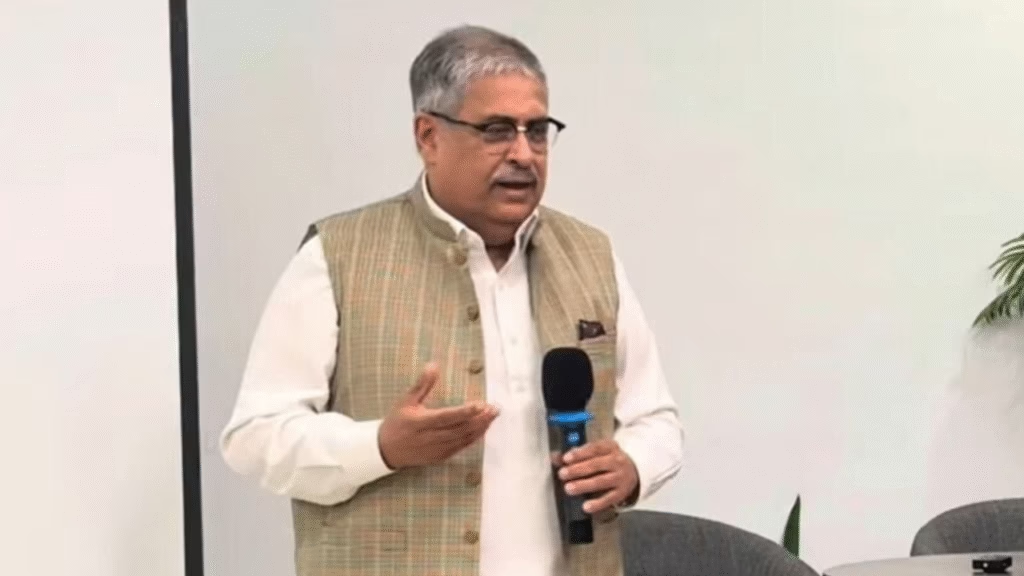

Supreme Court Justice Athar Minallah has raised serious concerns about Pakistan’s judicial system, questioning whether the country’s courts truly operate with independence. Speaking at a Defence of Human Rights event, Justice Minallah delivered pointed remarks about the challenges facing Pakistan’s judiciary and its ability to protect citizens’ fundamental rights.

The Independence Question

“Pakistan needs an independent judiciary and judges,” Justice Minallah declared, highlighting what he sees as fundamental flaws in the current system. His concerns center particularly on cases involving enforced disappearances, which he described as among the most challenging matters facing the courts.

The justice’s frustration was evident when he stated, “If the state is involved in missing persons cases, the courts cannot do anything.” This statement reflects the complex position judges find themselves in when state institutions may be implicated in the very cases they’re asked to adjudicate.

A Pattern of Interference

Justice Minallah’s comments gain additional significance when viewed alongside recent developments in Pakistan’s judicial landscape. In 2024, five Islamabad High Court judges took the unprecedented step of writing to the Supreme Judicial Council, alleging interference from executive branch officials and intelligence operatives in judicial matters.

The judges who signed this letter included Justice Mohsin Akhtar Kiyani, Justice Tariq Mehmood Jahangiri, Justice Babar Sattar, Justice Sardar Ejaz Ishaq Khan, Justice Arbab Muhammad Tahir, and Justice Saman Fafat Imtiaz. Their collective action underscored the seriousness of concerns about external pressure on the judiciary.

Responding to these concerns, Chief Justice Yahya Afridi’s National Judicial Policy Making Committee recently mandated that judges must report any external interference within 24 hours of experiencing it.

Personal Reflections on Justice

Justice Minallah shared personal experiences from his judicial career, particularly regarding missing persons cases. He recalled telling his staff, “I cannot tolerate missing persons cases in my area,” and emphasized that his court would show “no leniency to any government officer” in such matters.

The justice’s commitment to addressing enforced disappearances appears deeply personal. He noted that his judicial decisions on missing persons had “positive reverberations for four years,” suggesting that firm judicial action can make a meaningful difference.

The Balochistan Crisis

Particularly striking were Justice Minallah’s comments about the situation in Balochistan province. “Balochistan’s girls and women are crying on the streets; we should be ashamed,” he said, directly addressing what many view as systematic human rights violations in the region.

He revealed that Baloch students had approached the Islamabad High Court during his tenure there, despite the Supreme Court being a theoretically higher forum. “People had faith in the IHC and used to approach it from all over the country because the judges there were independent,” he explained, suggesting that public perception of judicial independence varies significantly between different courts.

Institutional Accountability

Justice Minallah didn’t spare his own institution from criticism. “Every judge of the Supreme Court is responsible for the violation of fundamental rights in Pakistan,” he stated, calling for greater judicial accountability and activism in protecting citizens’ rights.

He described writing to the Chief Justice about fundamental rights violations, noting that “nothing happened after I wrote the letter.” This admission reveals the limitations even senior judges face when attempting to address systemic issues within the judicial system.

Political Dynamics and Truth-Telling

The justice also touched on Pakistan’s broader political culture, observing that “those in the government have not been able to speak the truth for 77 years.” He noted how political parties “completely change after coming into the opposition,” suggesting a cycle where truth becomes secondary to political convenience.

Justice Minallah acknowledged the personal cost of speaking truth to power, noting that “the one who does [speak truth] is hated the most.” Yet he emphasized the transformative potential of honesty: “If we speak the truth, the situation will change.”

The Path Forward

While Justice Minallah’s remarks paint a challenging picture of Pakistan’s judicial system, they also suggest a path toward reform. His call for independent judges and judiciary comes with the implicit understanding that such independence requires not just structural changes, but also the courage of individual judges to resist pressure and speak difficult truths.

The justice’s comments occur against a backdrop of ongoing human rights concerns, particularly regarding enforced disappearances. Various human rights organizations have documented such cases, though government and state institutions consistently deny involvement.

Justice Minallah’s public statements represent more than judicial commentary; they constitute a call to action for Pakistan’s legal system to fulfill its constitutional role as protector of citizens’ fundamental rights. Whether this call will translate into meaningful reform remains to be seen, but his willingness to speak openly about these issues marks an important moment in Pakistan’s ongoing struggle for judicial independence and accountability.